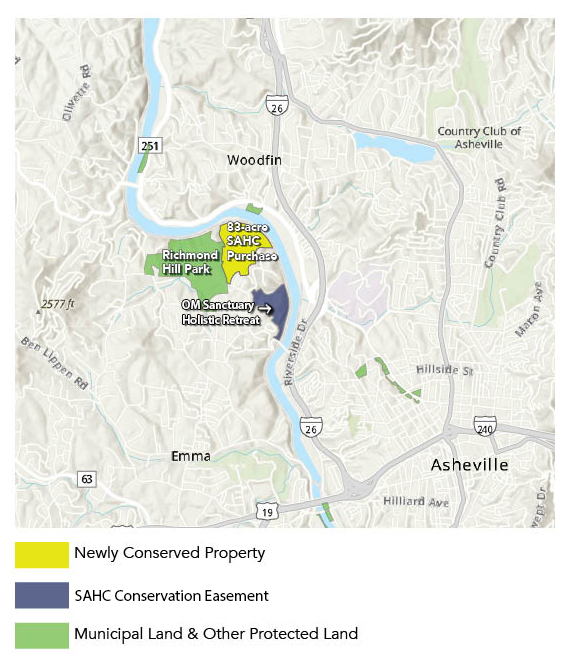

In March, the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy (SAHC) purchased 83 acres adjoining Richmond Hill Park for permanent conservation, ending a 4 1/2-year battle over the fate of the land.

The property, which straddles the boundary between the Town of Woodfin and the City of Asheville, was slated for development under two separate proposals. These proposals were ultimately scrapped in the face of intense local opposition, clearing the way for SAHC to purchase the land for conservation.

“This is a great outcome for this prominent forested bluff above a big bend in the French Broad River, especially in light of the shared desire among locals to support the river’s recovery from Hurricane Helene,” says Carl Silverstein, SAHC’s executive director.

SAHC is a nonprofit land trust conserving land and water resources in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee for over 50 years. Since 1974, SAHC has protected more than 90,000 acres.

SAHC hopes to add the tract of land to the City of Asheville’s Richmond Hill Park, which would increase the park size from 180 to 263 acres. In the meantime, the property is closed to the public as SAHC assesses damage from Helene and develops a land management plan.

But while conservationists won this round, they know the war isn’t over. The need for housing will mean that a proposal will arise in another area, posing its own set of tradeoffs.

Inside the battle over The Bluffs

SAHC first attempted to purchase the property in 2013 but couldn’t reach an agreement with the owner, who was holding out for a more lucrative offer from developers.

That offer came in 2020, when a Florida-based developer purchased the land and released its plans for The Bluffs at Riverbend, a mixed-use development that included more than 1,500 residential units, a 250-room hotel, a 59,000-square-foot office building, an amphitheater and a church. A bridge would be built across the French Broad River to handle the increased traffic.

By the developer’s estimates, the project would provide $1.5 million in annual property tax revenues to the Town of Woodfin, representing a 16.6% increase to the town’s budget, which was roughly $9 million in 2020-21.

Neighbors in both Woodfin and Asheville quickly organized to oppose the proposal, saying it would threaten water quality in the French Broad and overload the roads and infrastructure in the neighborhood. Together, they formed a coalition under the name Richmond Hill & River Rescue, put up a GoFundMe account to raise donations and hired an attorney to fight the proposal.

They also attracted the support of local environmental nonprofit MountainTrue, which stepped in to support the neighbors in their fight. In an online petition, MountainTrue argued that the site was unsuited to the intensity of the proposed development due to the steepness of the slopes, which drain into the French Broad, endangering water quality and the proposed whitewater wave and recreation park, which would be located just downstream.

The tactics worked. In 2022, after years of intense local opposition, the Bluffs developer scrapped the proposal and sold the parcel in an apparent victory for concerned neighbors.

The second and final battle

Except the battle didn’t end there. The property was purchased by a second developer — this one based in Delaware — who proposed building 650 residential units. No bridge was included in this second proposal, which was dubbed Mountain Village.

Once again, neighbors rallied to defeat the new proposal, which they argued was still out of scale with the fragility of the surrounding ecosystem.

In the summer of 2023, SAHC made another offer on the property. Again, it was rejected.

However, as opposition to the project dragged on, the developer began to change its tune. Permits for the second, scaled-down development were mired in the complex and time-consuming conditional zoning process.

Frustrated with the slow pace, the developer sued the Town of Woodfin. When that also failed to speed up the process, the conversation began to shift.

Neighbor and local business owner Shelli Stanback says bringing the various parties to the lawsuit together led to a breakthrough.

“I spoke about the Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Plan and how so many of us have dedicated decades of time, energy and personal resources to see that vision of a protected, accessible river corridor become reality. I wanted the developers to understand that our efforts were not just aimed at stopping a project — they were part of a long-standing commitment to a dream shared by many,” Stanback says.

Stanback is the CEO of OM Sanctuary, a nonprofit holistic education and retreat center next to the proposed development. Stanback had worked with SAHC to preserve its portion of the forest in 2014.

Stanback requested that SAHC be included in the roundtable conversation. “When I introduced Carl [Silverstein], he spoke sincerely and that moment of shared understanding apparently opened the door to ongoing dialogue.”

While SAHC had been engaged in the process from the start, this was the first time that the outcome seemed as if it might be tipping in its favor. By the spring of 2024, the developer and SAHC were engaged in regular weekly talks.

According to Silverstein, the developers became increasingly receptive to the idea of receiving another offer. SAHC leapt into action to raise the funds to purchase the property.

Last month, SAHC purchased the property for $12.4 million with the help of neighbors and private donors. After nearly five years, the battle was over.

An unusual choice

As with any proposed development, it pits against each other developers and housing advocates, who point to national and local housing shortages as evidence for why more development is needed, and neighbors and conservationists, who argue that preservation is the more sustainable choice.

“We know that we live in an area where affordable housing is a crisis,” Silverstein acknowledges. “The key to our conservation approach is balance. In this case, the property wasn’t the right location for a high-density development.”

At first glance, the 83-acre Richmond Hill property was an unusual choice for SAHC, given its proximity to Asheville’s urban core.

“Most of our conservation projects have been in more remote places,” says Silverstein. Previous SAHC purchases have adjoined the Appalachian Trail corridor, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Mount Mitchell State Park.

“SAHC strives to protect the things that people love about this region — the scenic beauty of the mountains, parks and public lands for all people to enjoy outdoor recreation, habitat and wildlife corridors that support a plethora of species, and clean water sources for drinking and for recreation activities like fishing or kayaking,” says SAHC’s communications director, Angela Shepherd.

The Richmond Hill property met all of these criteria. The tract is one of the last undeveloped parcels along the French Broad River near Asheville. It adjoins Richmond Hill Park and the state-designated Richmond Hill Forest Natural Area. It overlooks the French Broad River, providing scenic views.

The trade-offs of conservation

Beyond the views, the water that flows down the property’s steep slopes empties directly in the French Broad River.

“Seeing hundreds of landslides as well as businesses and homes washed away in Hurricane Helene underscored the importance of protecting our floodplains and forested slopes to soak in and filter stormwater, protect important riparian species and help reduce future flooding,” says Hartwell Carson, clean waters director for MountainTrue.

In addition, the property contains streams, wetlands and vernal pools, which provide habitat for local flora and fauna. Richmond Hill Park and the adjoining lands are home to several rare species, including the mole and southern zigzag salamanders, nodding trillium and eastern fairy shrimp.

Local land development planner Scott Adams, who volunteers with the pro-housing nonprofit, Asheville for All, acknowledges the valuable ecosystem services that conserved land can provide but pointed out that all land-use decisions come with trade-offs, including potential downsides for conservation elsewhere.

“Where will those original 1,500 housing units be built now? The demand for those will go somewhere,” Adams points out.

Adams argues that unless Ashevilleans can agree on places in town where major housing developments can be built, these types of projects will continue to be pushed farther out from the city center, where they are more likely to disrupt intact forests and farmland and contribute to urban sprawl.

“In my view, this all points back to the benefits of policies like the ones the Asheville City Council passed in March that make it easier for large residential projects to be built on our major corridors, where they belong,” says Susan Bean, director of housing and transportation for MountainTrue.

Adams agrees. “We can have housing and retain portions of urban forests.”