West Asheville has maintained an identity so distinctive that visitors frequently ask if it’s really part of Asheville. That’s not surprising, considering the area’s history (see timeline, “Notable Moments”). It actually was a separate town during two brief periods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And when West Asheville voted on consolidation with Asheville in 1917, residents were evenly divided: Merger supporters carried the day by a mere eight votes, the Asheville Citizen reported on June 10. In an editorial that same day, the newspaper’s editors emphasized growth, noting that West Asheville’s 6,000 residents brought Asheville’s population to 30,000.

More attention was given to the voting method, however: It was the first election in Western North Carolina to use a secret ballot.

Although West Asheville wasn’t defined as a place until the Post Office gave it that name in the late 1880s, human beings have lived in and around the area for about 10,000 years. The earliest known inhabitants were various American Indian cultures; the cherokee came later.

• 1776: William Moore fords French Broad as part of Gen. Griffith Rutherford’s expedition to subdue the Cherokee.

• 1777: Moore returns with slaves, builds blockhouse fort near Hominy Creek.

• 1827: Revolutionary War veteran Robert Henry and his slave, Sam, discover sulphur springs in what’s now Malvern Hills.

• 1830: Reuben Deaver, Henry’s son-in-law, builds the Deaver’s Springs hotel, inaugurating Asheville’s first wave of tourism. Visitors, mostly from South Carolina, follow Haywood Road, part of the Western Turnpike that runs from Salisbury, N.C., to the Georgia state line.

• 1833: James McConnell Smith builds the first bridge across the French Broad, replacing Jarrett’s Ferry. Smith charges 25 cents for a driver with a team and buggy, 6 cents for a foot passenger.

• 1861-65: On Jan. 13, 1861, Cornelia Catherine Henry, who’s living near the sulphur springs, writes: “Cold and windy … the war has commenced in Charleston, South Carolina.” With most men gone, it’s left to the women to tend the farms, raise the children and and sell what crops they can.

• 1885: Edwin G. Carrier buys 1,200 acres of land west of the river (including the sulphur springs), develops Haywood Road and builds the Carrier Springs Hotel (the earlier hotel having burnt down) and a racetrack along the French Broad.

• 1889: Carrier’s West Asheville Improvement Co. obtains incorporation papers for the town.

• 1891: Carrier’s West Asheville and Sulphur Springs Electric Railway begins operation, crossing the river on Carrier’s Bridge along Amboy Road.

• 1892: Carrier leases the hotel to nationally known physician Dr. Carl Van Ruck. The hotel, renamed The Belmont, later burns to the ground.

• 1895: Swannanoa Country Club founded, with a clubhouse near the springs. It later moves to North Asheville, becoming the Asheville Country Club.

• 1897: Rutherford P. Hayes, son of former President Rutherford B. Hayes, buys a 1,200-acre farm, builds cabins for friends and guests, and establishes an experimental agricultural station. His home still stands at 93 Blue Ridge Ave.

• 1897: The town’s incorporation is repealed.

• 1903: Dr. Lucius Compton establishes Faith Cottage for unwed mothers and their children.

• 1906: Compton buys an aging cabin and 4 acres of land, establishing Eliada Home for Children.

• 1911: E.W. Pearson becomes Hayes’ agent for a new African-American development on Buffalo and Fayetteville streets. Pearson later becomes first president of Asheville’s NAACP chapter.

• 1913: West Asheville re-incorporates.

• 1917: West Asheville and Asheville merge. West Asheville votes 169 to 161 for consolidation; Asheville’s tally is 364 to 157. Turnout is light; the campaign focuses on creating a greater Asheville.

• 1880s – 1930s: West Asheville develops as a community rather being noted solely for its sulphur springs. Various types of trolleys operate along Haywood Road, which was built to accommodate their climb up from the river.

• 1950s – ’80s: Patton Avenue becomes the principal traffic corridor, drawing business away from Haywood Road.

• 1990s: Drawn by lower rents, younger people begin moving into West Asheville and starting businesses along Haywood.

• 2000s: West Asheville renaissance is in full swing.

• 2000: West Asheville Development purchases historic buildings on Haywood Road and begins renovation.

• 2001: Cathy Cleary and Krista Stearn — two of West Asheville Development’s co-founders — open the West End Bakery.

Sources: West Asheville History Project; Asheville Citizen-Times; North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library; Asheville’s African-American Black History Timeline, radio station WRES-LP.

It wasn’t until the late 18th century that outsiders began having a significant impact. William Moore and his slaves built a fort near Hominy Creek in 1777. And the 1827 discovery of sulphur springs marked the beginning of Asheville’s reign as a tourist destination.

The pace of development stepped up considerably in 1885, when Edwin G. Carrier stopped off on his way to Florida from his home in Michigan. Buying 1,200 acres of land, he developed Haywood Road, built the Carrier Springs Hotel and constructed a racetrack along the French Broad to entertain guests.

Four years later, Carrier’s West Asheville Improvement Co. obtained incorporation papers for the town. The post office was renamed, and Samuel Doak Hall became the first mayor.

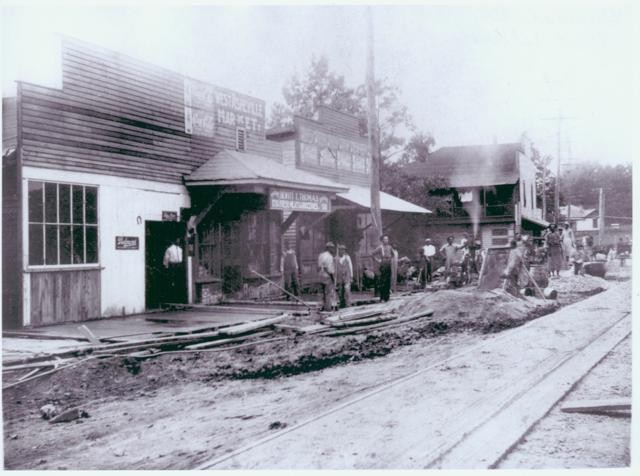

Carrier’s West Asheville and Sulphur Springs Electric Railway began operation in 1891, crossing the river on Carrier’s Bridge along Amboy Road. Various trolleys ran along Haywood Road (which was built to accommodate them, the existing road being too steep a climb up from the river) until 1934. During that span, West Asheville developed as a community rather than simply being noted for its sulphur springs.

Nonetheless, in 1897, the town’s incorporation was repealed, for reasons that remain unclear. On March 13, 1913, however, West Asheville was re-incorporated.

By 1915, West Asheville’s 4,000 residents were served by 10 stores, a mission, a volunteer fire department, a bank and an asphalt boulevard 60 feet wide and more than a mile long. Faced with growing municipal debt and increasing pressure for expansion and various improvements, however, the mayors of both Asheville and West Asheville urged annexation.

The merger came to pass on June 9, 1917. Voter turnout was light: West Asheville voted for consolidation 169 to 161; Asheville’s tally was 364 to 157.

Many years later, former Asheville Police Chief Charles W. Dermid, who grew up in West Asheville, told Citizen-Times reporter Henry Robinson that many improvements were in fact made, including paving streets and installing sidewalks. Following consolidation, West Asheville shared in the city’s boom period, which lasted until the Great Depression.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the emergence of Patton Avenue as the principal traffic corridor drew attention (and business) away from Haywood Road. But in the 1990s, younger people began moving into the neighborhoods off Haywood, taking advantage of lower home prices. They also started opening small businesses along what had traditionally been West Asheville’s main thoroughfare, sowing the seeds for today’s bustling community.

“West Asheville has had its boom cycles, then it has had times when it was not as successful,” notes librarian Karen Loughmiller, coordinator of the West Asheville History Project. “The older neighborhoods in West Asheville are still intact. We have developed a nice mix of younger folks and older folks; it’s a very walkable area.”

Asheville’s new Haywood Road Vision Plan, approved by City Council Feb. 25, points out that “In some ways the Patton Avenue ‘bypass’ construction saved Haywood Road from additional widening projects that were so common on many roads around Asheville and allowed the community to maintain its historic walkable character. Merrimon Avenue provides a good contrast to Haywood Road, since it is a local roadway that has been widened over time to four lanes. The resulting larger scale and faster driving speeds along Merrimon have made it difficult to redesign and return it to the pedestrian-friendly format so valued on Haywood Road.

“Because Haywood Road has retained more of its original scale, it has developed strong community support for strengthening its pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use character. It is along this historic roadway that the community now thrives.”

— Grady Cooper can be reached at gcooper@mountainx.com.

2 thoughts on “A shifting identity: West Asheville’s storied past”

Whoa wait a second! Hold on! You mean the absolute golden value that is Haywood Road now, is due to not transforming it into a major highway thoroughfare like Merrimon Avenue, and the bustling period of commercial activity ended at the Great Depression? No. That is just crazy talk. Where’s the part about Haywood Road being and industrial transportation corridor, connecting the world with the major industrial output of what is now known as the River Arts District? Where is that part of history?

Haywood Rd., is tied to the Western Turnpike for horse, wagon, and later, automobile transportation. The River Arts District is due to the old railway depot which stood until 1968.on Depot St. and its surrounding businesses, all linked to the downtown Asheville world.