“All contemporary art conversation is about contemporary culture,” says artist Mel Chin. “That conversation is not complete without talking about sports.” He’s referring to “Growth of the New Gods” — the massive grapevine of basketballs and leaf-shaped hoop-netting that festoons the Asheville Art Museum’s façade on the Biltmore Avenue side. The bright orange globes are an unexpected sight for passersby, and signal the arrival of Chin’s anticipated Asheville exhibition, High, Low and In Between, on display at the museum through Nov. 25.

The basketball grapevine is an Asheville variation of Chin’s 2011 “Temple of the New Gods,” wherein the postmodern foliage covered the Greek revival façade of the Nave Museum in Victoria, Texas. The installation illustrates the loaded symbols and dry wit conveyed in many of Chin’s sculptures.

"We're talking about gods; we're talking about the primacy of sports figures in terms of people we listen to,” says Chin. “And they are superhuman in their prowess and capital."

Need more Chin?

If Chin's exhibit leaves you wanting more, pick up a copy of Do Not Ask Me, a collection of key works exhibited at The Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston in 2006. Do Not Ask Me is available at the Asheville Art Museum’s bookstore

Thoughtfully written essays accompany a dazzling assortment of photographs of Chin’s socially and politically motivated art works. Loom, a disquieting installation wherein a multitude of eyes peer out from brown soil piled onto the museum’s floor, commemorates the victims buried in mass graves at the hands of Guatemalan death squads. “[Chin] is the only artist I know who could embellish torture, and murder and violence without resorting to pornography,” writes Paul Farmer in an essay, “Buried With Their Eyes Open.” “I left the gallery wondering if the dead had finally been buried properly, all eyes closed except ours; for we, somehow complicit in their murders, have had ours opened.”

Do Not Ask Me also contains a complete reproduction of 9/11 – 9/11, a zine made in 2002 by Chin that weaves together the 1973 coup d’état organized by the Chilean military (unofficially endorsed by Nixon and the CIA) with the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Towers. In collaboration with a team of Chilean animators, in 2006 Chin produced an animated film based on his zine. 9/11-9/11, the movie, will be screened at The Asheville Art Museum on Sept. 11 at 5:30 p.m. Chin will be in attendance to discuss the film.

Born to Chinese immigrants in Texas, Chin grew up in Houston and currently lives in Burnsville, N.C. Over the last 40-plus years, he has developed a number of projects that would be impossible to contain within the walls of a museum, such as his ongoing project Operation Paydirt. The large community endeavor aims to collect 300 million hand-drawn interpretations of the U.S. $100 bill — dubbed “Fundreds” — to be delivered to Congress in exchange for $300 million, the estimated cost of cleaning lead-contaminated soil in New Orleans, according to the project's website, http://www.fundred.org.

“I still believe art is a catalytic structure that actually forms a place for discourse, or even a place for language to be created,” says Chin.

Most astounding is the array of materials and forums Chin has accessed in his art work. His 2001 project, S.P.A.W.N., facilitated the development of earthworm farms in the basements of burned and abandoned homes in Detroit (the acronym stands for Special Project: Agriculture, Worms, Neighbors).

“Revivial Field,” built on a landfill in St. Paul, Minn., incorporates hyperaccumulators — plants that absorb heavy metals and other toxins in soil.

When asked if all of his work is politically motivated, Chin responds, “To be honest, you can’t open your mind or be in this world without being politically based. Inaction is equivalent to action itself. If someone wanted to make those distinctions they can, but in my mind, I don’t.”

Updating the image context

Look it up … somewhere else

Even though Mel Chin and his crew of assistants began working on “The Funk & Wag, from A to Z” more than a year ago, its 2012 debut couldn’t be more pertinent.

In March, reference-book mainstay Encyclopedia Britannica announced that the 2010 publication of its 32 volume set would be its last. This marked the end of the 242-year run for English language encyclopedia.

The first edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica was published in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1771 as a three-volume set. Conversely, the last and final edition, printed in 2010, was a behemoth. The combined 32 volumes weighed 129 pounds and had a price tag of more than $1,400.

Only 12,000 sets were printed, of which a few thousand are still available. Some were undoubtedly graduation gifts, but a large portion most likely joined ranks of fellow volumes, past and present, in a more common function: decoration.

As for Funk and Wagnall’s, named after founders and former classmates Isaac Funk and Adam Wagnalls, its last encyclopedic edition was printed in 1997. But what set this company apart — and more specifically the 1953-56 encyclopedic edition that Chin used for the exhibition — from others of its time was accessibility. In 1953, the Funk and Wagnall’s Standard Encyclopedia could be purchased in supermarkets throughout the United States.

In an odd twist of fate, the Houston supermarket owned and operated by Chin’s parents did not sell the volume. "My parents couldn't afford to have them in their grocery store in the Fifth Ward," Chin told the Houston Chronicle in an April 6 story. — Kyle Sherard

Visitors to the Asheville Art Museum have the opportunity to see a sample of Chin’s more material pursuits. The largest component of the exhibition is “The Funk & Wag, from A to Z,” a monumental endeavor of 524 collages that cover the walls of the museum’s East Wing gallery. Each collage was hung with scrupulous care by two of the museum’s art handlers, and the piece took nearly three days to install.

Entering the gallery brings to mind the hushed reverence of an old library, except here the books’ contents are on display. To prepare the collages, Chin had every image excised from the complete collection (25 volumes) of a 1953 edition of Funk & Wagnall’s Universal Standard Encyclopedia, once regarded as the ultimate resource of knowledge and information.

Not only is the overall presentation striking, but each collage offers a poetic investigation of Chin’s creative mind; this just might be one of Chin’s most personal pieces to date. Formally there is a lot to study, like Chin’s restrained compositional style and the use of paper as a medium, whether it’s woven together, assembled into a nest, torn or hole-punched.

Many of the collages are quite witty: the owl with bat-like wings made of buildings, or the robotic lizard-like creature. No doubt everyone will draw their own conclusions of what each piece means, and for those who want guidance, a title catalogue is available, which reads as a book of poems on its own. “Arch Rivals,” a collage composed with aqueduct arches, is probably funnier with the title, but the entire collection is just as good without the wordy references.

It becomes clear after looking through the collages that, in 1953, encyclopedias contained a disproportionate amount of images of white-male thinkers, architecture and animals. So Chin has achieved a major feat: he has liberated the antiquated knowledge that upholds a paternal, Euro-centric outlook on the world. Here, a viewer’s subjective mind is free to roam. “The visual information in these 1950’s sets were contextualized by texts that may be outmoded today… [’Funk & Wag’] is an upgraded, or updated, re-contextualization of all the images,” says Chin. “It’s a new life.”

An essential element of Funk & Wag is an unassuming circular bookshelf that references Queen Anne furniture (“My least favorite furniture style of all time,” says Chin). The bookcase is specially designed to accommodate the remains of the hardbound encyclopedias, which, after their vivisections, close into wedge-like forms. The shelf holds them in rounded unison like slices of a pie. A portion of the case encapsulates the remaining shreds of paper behind glass, so that no part of the book was actually thrown away. “If you wanted to, you could unglue every collage and you could reconstruct the entire encyclopedia set,” says Chin. “No book was destroyed in the making of this [artwork].”

Hillbilly armor

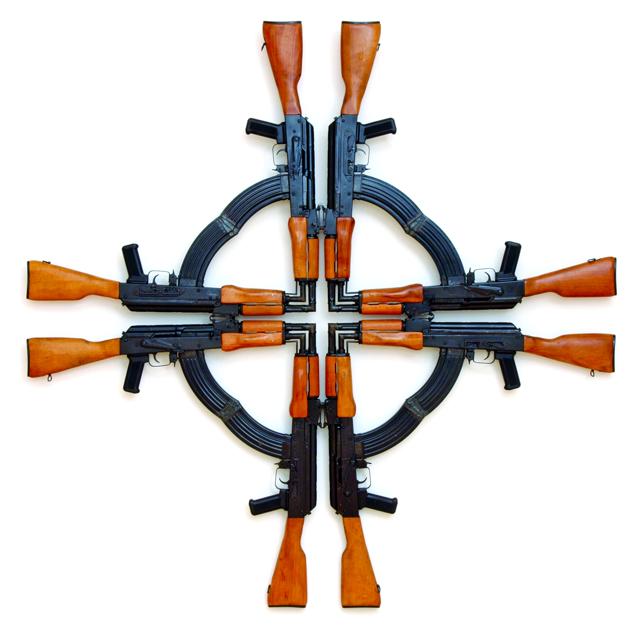

Themes of war and institutionalized violence have weighed heavily in Chin’s work throughout the years, as two sculptures at the museum exemplify. One, the “Cross for the Unforgiven,” is an elegant configuration of AK-47 assault rifles welded into the Maltese cross of the Crusades, and serves as a reminder of a long history of conflict in the Middle East.

The other, “Terrapene Carolina (Hillbilly Armor),” is a re-creation of armor in the shape of a turtle’s plastron as the underbelly of a U.S. Army Humvee. It is constructed out of rubble gathered from Tennessee and North Carolina: a block of concrete, a tin roof, windows from a schoolhouse, a compacted shopping cart, the side of a trailer. The varied surfaces of debris suggest the assorted histories of individuals sent into battle.

The sculpture is a response to Donald Rumsfield’s 2004 comment, “You go to war with the army you have,” directed at U.S. soldiers dissatisfied by the lack of armor on their Humvees. To up-armor their vehicles, soldiers scavenged landfills in Tennessee for pieces of scrap metal and bulletproof glass to bolt to their Humvees as added protection against roadside bombs in Iraq. They called it "hillbilly armor.”

The exhibit’s title, High, Low and In Between, references a song by the late Texas musician Townes Van Zandt, a lifelong friend of Chin’s. “The highs are humor, expression, life, love and all that,” says Chin. “The lows are death, war, destruction, depression, solitude. Sometimes the high can be solitude; they’re permeable by definition. But everything in between is the funk and wag.”

— Ursula Gullow writes about art for Mountain Xpress. See her work at http://ursulagullow.com.

what: Mel Chin: High, Low and In Between

where: Asheville Art Museum

when: On view through Nov. 25 (Details and associated events at ashevilleart.org)

Image credits: Mel Chin, Cross for the Unforgiven, 2002, AK-47 assault rifles (cut and welded), 59 x 59 x 1.5 inches. Image Courtesy of Station Museum of Contemporary Art. Photo by John Lucas. Mel Chin’s The Elementary Object, 1993, Corsican briarwood, steel, plastic, concrete/vermiculite, excelsior packing material, flannel, paper tag, fuse cord, triple F blasting powder. 3 1/2 x 12 1/2 x 10 1/4 inches. Multiple of 13. Image courtesy of Mel Chin.