In case you didn’t know, The Asheville Art Museum is free to the public for two hours the first Wednesday of every month. You read that right: Every first Wednesday of every month the museum waives its admission fee from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m.

So if you are reading this article fresh off the presses, maybe you can take a quick jog down to the Asheville Art Museum on your next coffee break and check out the Sewell Sillman exhibit on the top floor of the building. The exhibit will end on Sunday, Jan. 9, so only a few days remain to see it. If you miss this month’s free Wednesday you might consider paying the admission fee and joining one of the curators for a tour of Sillman’s work on Friday, Jan. 7 at noon.

There is scant record of Sewell Sillman, the visual artist. He is better known as the person responsible for half of the art publishing team, Ives-Sillman Inc. a print business that created silk-screened prints for well-known artists like Jacob Lawrence and Piet Mondrian. Sillman also worked closely with famed colorist Josef Albers and produced many of Albers’ art prints.

Also at the museum

You can always get a membership to the Asheville Art Museum and go whenever you want. Benefits include access to the museum’s library and free admission to museum events.

Also showing at the Asheville Art Museum: an exhibit called The Director’s Cut: Museum Executive Director Pam Myers has chosen works from the museum’s permanent collection. The mish-mash of styles is extreme, but worth a visit if only to see the painting by Zelda Fitzgerald. Through March 13.

And, The Olmsted Project: Photographs by Lee Friedlander. Black-and-white photographs by Friedlander that showcase details of public spaces originally designed by the father of American landscape architecture: Frederick Law Olmsted. Through April 24.

—U.G.

What is known about Sillman is that he was born in 1924 and died in 1992. He attended Black Mountain College before graduating from Yale University in 1962. His visual art was rarely, if ever, exhibited before his death. One can only wonder whether his close proximity to so many established artists hampered his own identity as an artist.

Sewell Sillman: Pushing Limits is the first time that these particular Sillman pieces have been presented publicly. There is something eerie about seeing a lifetime of work that describes an otherwise nondescript person. Much of the exhibit’s allure lies in the fantasy that many artists secretly harbor: Being “discovered” without having to deal with the riff-raff of an inscrutable art world.

According to Cole Hendrix, assistant curator of the Asheville Art Museum, Sillman worked as a printmaker and teacher, but was very private about his own art-making. In spite of his absence from the public art scene, Sillman kept his work well-organized and packaged in archival boxes. “Obviously he had an awareness and some pride in what he was doing,” says Hendrix.

The collection at the museum represents three distinct phases of Sillman’s creative evolution. The first: Color prints produced shortly after Sillman’s stint at Black Mountain College, reflecting Albers’ obvious influence on Sillman.

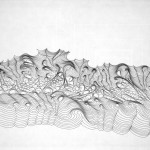

The second phase is Sillman’s exploration of line in the late ‘60s, and the work is as much about the process of making it as about the final product. Here, Sillman has drawn contours of syncopated lines hundreds of times, reflecting the infamous Albers’ assignment to “draw a continuous broken line.”

At first glance, the lines look like they might have been produced via machine, but the hundreds of contoured waves that ebb against each other reveal a human’s hand at work. “I can’t even imagine the kind of patience required to make this kind of work,” says Hendrix.

In the 1970s, Sillman made a shift to watercolors and the works culled from this period of his life are geometric studies using a limited color palette. Says Hendrix, “It’s another example of Sillman setting a strict set of rules for himself and then figuring out the visual possibilities.”

The last works of Sillman’s life are his gravest. At this point Sillman knew he was dying and the meticulously inked gradation of grays of these paintings merge together like a solemn death march. The interlocking shapes create the illusion of the feathers of an arrow, lending a descriptive name — flèche, from the French for arrow — to these works. In “Swarm,” one of the last pieces Sillman ever produced, black shapes emerge in a visual notation and may well be considered Sewell’s final masterpiece.

To find out more about events and exhibitions at the Asheville Art Museum visit ashevilleart.org.

— Ursula Gullow writes about art for Mountain Xpress and her blog, artseenasheville.blogspot.com.